Article • Significant improvement in cleaning, disinfection and sterilisation

Surgical robots must also be hygienic

Modern healthcare without hand hygiene? Inconceivable – particularly in the operating room (OR). But what happens when it is not the surgeon who handles the scalpel, but a robot?

Report: Wolfgang Behrends

Robotic surgery, just like surgery performed by humans, always carries a risk of microbial transmission to the patient, says Professor Johannes K-M Knobloch of University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE).

A specialist in microbiology, virology and infection epidemiology and Head of Hospital Hygiene in his institution, Knobloch explains how robotic systems are cleaned, disinfected and sterilised to prevent infections.

Several surgical robots work at UKE in Hamburg, where the Da Vinci systems are mainly used for prostatectomies and for intra-abdominal surgery. ‘The robotic arms themselves are hardly subject to contamination,’ microbiologist/virologist Knobloch explains, ‘since the systems have a smooth surface and were designed to be cleaned easily.’ For most minimally invasive procedures the surgical robots are equipped with click-on devices that are removed after surgery and cleaned, disinfected and sterilised separately.

Smaller and more complex

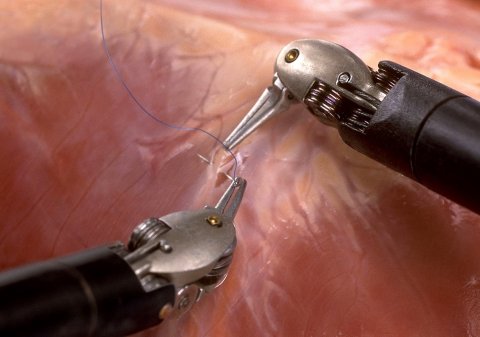

The array of instruments available to the surgical robot corresponds largely to what is available to human surgeons – often in miniaturised form and with some adjustments. The robot, for example, does not cut with a sharp knife but burns tissues with electro-cauterisation.

© Intuitive Surgical, Inc

The robotic instruments often contain tiny mechanical components. In surgery, graspers, clamps or needle holders with a complex Bowden pulley mechanism are used. This construction, which is necessary for the robot to be able to position the instruments more precisely in the body, comes with a drawback, Knobloch finds: ‘Cleaning and disinfecting is much more complicated than with a conventional one-piece scalpel.’

From the hygiene aspect, the thin wires that open and close, tilt and angle the instruments present a challenge. ‘During interventions, these wires move back and forth many times. With each pull they also pull contaminated material, such as tissue, blood and protein from a patient’s body,’ the hygiene expert explains; indeed ‘in the early days of robotic surgery, it was a real problem to remove all protein particles from the robot parts and prepare them for the next patient.’

© BANDELIN electronic GmbH & Co. KG

From the OR right to the cleaners

You need to handle these robotic instruments on a daily basis and get to know them; otherwise your cleaning might result in errors

Johannes Knobloch

With technology progressing, cleaning, disinfection and sterilisation also improved significantly. To avoid protein drying and caking on the instrument, the parts are submerged in a cleansing solution immediately after an intervention. Special ultrasound baths remove most of the particles. In a final step the instruments are treated in a thermal washer-disinfector. Modern surgical robots feature specific connectors which allow thorough cleansing. ‘This sophisticated multi-step procedure can only be performed by specially trained staff. You need to handle these robotic instruments on a daily basis and get to know them; otherwise your cleaning might result in errors,’ Knobloch says. Therefore, at UKE robot parts are cleaned, disinfected and sterilised separately from conventional OR instruments.

Additionally, manufacturers of surgical robots provide guidance about cleaning and disinfection of their products. The recommendations are to a large extent the result of learning processes by clinicians and manufacturers alike, says Knobloch: ‘User feedback has contributed a lot to the development of cleaning best practices. The manufacturers use clinicians‘ feedback, integrate it and pass new recommendations back to the surgeons who provide feedback again. Over the past few years, this feedback loop has led to sophisticated cleaning/disinfection documentation.’

© Intuitive Surgical, Inc

Due to their complex architecture, the cleaning and disinfection procedure for robotic instruments is much more time-consuming than that of conventional surgical instruments. ‘The effort, however, is worthwhile.’ Knobloch believes, ‘since experienced operators of surgical robots achieve better patient outcomes. The smaller incisions performed by the robots translate into less bleeding and fewer infections. Furthermore, patients can be mobilised faster because their abdominal muscles remain intact.’

The expert’s summary is positive: Surgical technology and post-surgical treatment might be more expensive and more time-consuming than conventional approaches, but the benefits clearly outweigh these disadvantages.

Profile:

Professor Johannes Karl-Mark Knobloch is a specialist in microbiology, virology and infection epidemiology and head of the hospital hygiene department at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE). His research focuses on the development of microbial biofilms, for example on implants. He is a member of the German Society for Hygiene and Microbiology (DGHM) and the German Society for Hospital Hygiene (DGKH).

08.01.2020