Meeting the needs of different cultures: Germany

Migrant medicine as a course for German medical students? This is a unique concept in a country where it is currently only being offered at the Justus Liebig University in Giessen.

Since 2004 trainee medical doctors have been able to spend a term learning about dealing with migrants and facing new types of problems with future patients. How does one deal, for instance, with a patient who doesn’t speak a word of German?

Almost 10% of Germany’s population is now of foreign origin, with Turks, Kurds and Arabs making up the largest group, followed by migrants from former Yugoslavia. For medical students spending time on hospital wards for the first time this means every tenth patient they face is different.

Giessen University Hospital has been tending migrants in their own languages for almost 20 years. The department responsible for treatment of out-patient migrants has access to an interpreter service offering 40 different languages.

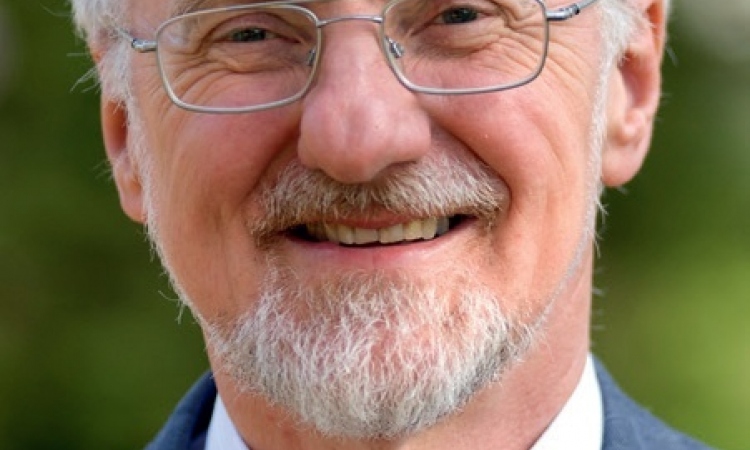

‘Because of our migrants’ clinic we obviously also have many more foreign patients on the wards than other hospitals,’ explained Dr Ahmet Akinci, consultant at the Medical Clinic II at Hanau City Hospital. ‘We realised that out students have always been interested in finding out something about the specific diseases or psychological problems among this group of patients and also in better understanding their culture-specific behaviours, which is why we thought of offering the course Migrant Medicine – Interdisciplinary Aspects of Medical Care for Patients with a Background of Migration. Dr Akinci is a member of the Migrant Medicine working party at Giessen University and has no complaints about a lack of interest in his subject: ‘So far, the seminars have always been full. However, we try to limit the groups to between 20 and 25 participants to create a relaxed atmosphere. Every term I take two or three patients to the lecture; of these, at least one doesn’t speak a word of German. When I ask my students to find out what the problem is with this foreign language speaking patient they eventually understand this intercultural problem.’

The objective of the course is for the students to develop a certain intuition in dealing with foreign patients and to gain an overview of certain migrant-specific disease patterns. ‘When a trainee doctor doesn’t know that every third Arab over the age of 50 suffers from diabetes then, of course, he is surprised that every diabetes test from patients originating from this region is positive. These facts are commonly known, but are often not taught to students by university professors. Again and again, even I encounter cases at the migrant treatment department that I’ve never seen before – be it an unknown type of worm in the intestine of an Indian patient, which he has harboured for years, or a Turkish family of nine, all of whom want to be simultaneously tested for Hepatitis B in my cubicle. Of course I also discuss these types of cases with my students.

‘At the beginning of term I initially discuss the basic question: What does migration actually mean? What are the reasons for it? What is the current situation in Germany, i.e. which are the countries where most migrants originate and where do many of them tend to live?’ In the next stage, the students – who, he points out, also come from very mixed ethnic backgrounds – are familiarised with ways of thinking and cultural differences among patients with a background of migration. ‘Once a term we hold a joint film evening where we show productions that relate to migrant-specific problems. In the course, comprised of ten double-periods, we also have many guest lecturers from different fields who examine the topic from different angles. At the end, we ask the students to write a report about their personal encounters with migrants. Many visit areas that have a particularly high ratio of migrants for this purpose. Above all we want to teach them that cultural diversity can be an obstacle – but not one which cannot be overcome

17.02.2009