Heart in hand

John Brosky reports

Surgeon Alain Carpentier is ready to remove a patient’s heart and replace it with a mechanical device he spent 15 years developing. By 2013 the procedure will be performed on 50 European patients as part of a clinical trial to win CE approval for the world’s first fully implantable artificial heart.

This year 100,000 people will be diagnosed with severe heart failure and learn they have about 12 months to live as their heart loses its ability to pump blood.

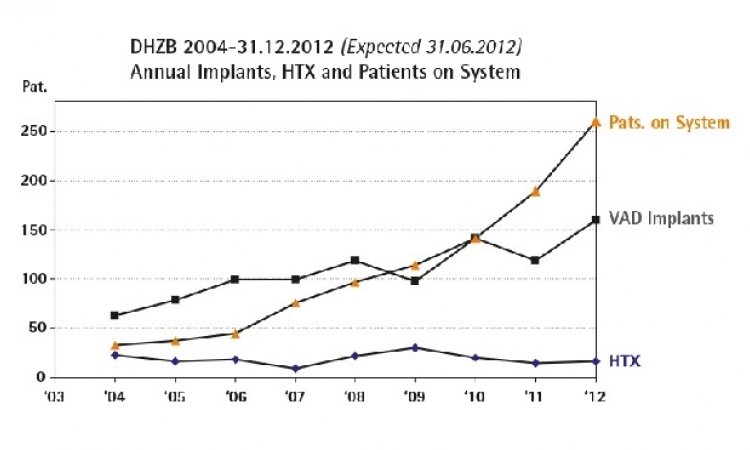

One out of 10 of these patients will receive a heart transplant, while some will be connected to a ventricular assist device (VAD) as a bridge-to-transplantation to extend their life for a couple year in the hope a suitable donor heart will be found.

Each year in Europe 50,000 people with heart failure die, having run out of options.There simply are not enough hearts to go around, and most people with severe heart failure lose the race against the clock.

“Even the great news that someone will receive a new heart is sadden by the fact that someone died for that heart to become available,” said Alain Carpentier, MD.

“And we have reached the limits of what can be done with VAD, which ultimately is temporary, palliative care,” he said. “I have always been convinced that more could be done to help these patients,” he said.

In June, 2010, Dr. Carpentier, a Paris-based heart surgeon and internationally renowned inventor of heart devices, introduced a startling break-through in the fight to survive heart failure with the world’s first biocompatible, fully implantable, fully functional mechanical heart.

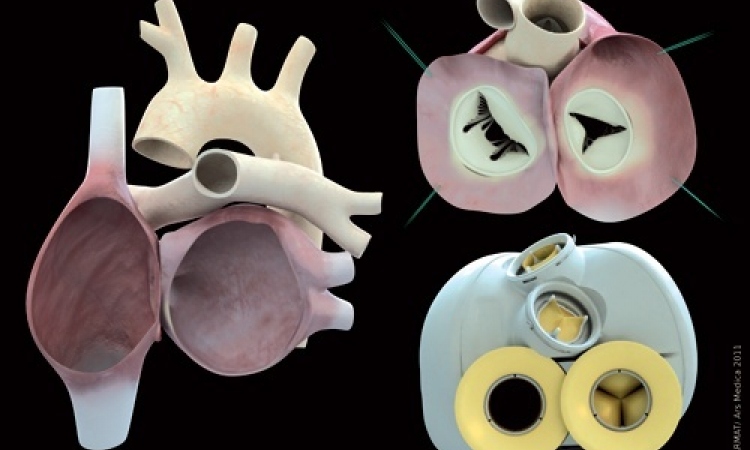

Carpentier’s artificial heart takes up the same space in the chest cavity as the human heart it replaces.

To power the micro pumps and continually relay data on the device function, a wire runs under the skin from the artificial heart to a small port above the ear where it exits the body and descends to a shoulder harness that holds a battery pack and a data transmitter.

The battery is good for five hours of operation, and patients can also bring along an adapter when visiting friends to plug into an electrical wall socket.

“What we have created is not a crutch to assist a patient for a few years but a fully implantable human heart replacement to provide an high quality of life beyond five years,” Dr. Carpentier told European Hospital.

Patients will not be attached to bulky VAD pump wheeled around on a caddy, he said, indicating a poster promoting his new heart that shows a patient riding a bicycle.

Nor will the device require an complex regime of medications to fight rejection of the transplanted heart, he said, as the 40 components of the Carpentier heart use only materials already approved for biocompatibility.

In July Carmat SAS, the company created to transfer Carpentier’s technology from the laboratory to the commercial market, launched a public stock offering that exceeded analysts’ expectations, raising more than €18 million.

Carmat said it plans to use the fresh capital to finalize pre-clinical testing of the device and finance the manufacturing of up to 40 hearts.

The first-in-man implantation is planned for the end of 2011, and by 2013 more than 50 patients in France, Germany and Italy will receive an artificial heart as part of the pre-clinical testing program that Carmat says it hopes will lead to a CE mark by the end of that year.

Carpentier’s first international recognition came in the 1960s when he used pig-tissue valves mounted in Teflon-coated metallic frames to solve the problem of clot formation with artificial heart valves.

The success of the valve led to a collaboration with the American inventor Lowell Edwards on a series of valves and devices that today continue to be the reference in heart surgery and are behind the commercial success of Edwards Lifesciences.

Carpentier’s continual improvements to prosthetic mitral and aortic valves was recognized in 2007 with the prestigious Lasker Award that praised his work for having prolonged and enhanced the lives of millions of patients with heart disease. Twenty-eight Lasker laureates have gone on on to receive the Nobel Prize in the last 20 years.

In his work at the Georges Pompidou Hospital in Paris, Carpentier saved the lives of several prominent men, who also happened to be friends and key customers of French billionaire Jean-Luc Lagardère.

The founder of the European Aeronautic Defence and Space Company (EADS), Lagardère was intrigued by Carpentier’s determination to build an artificial heart and provided his unconditional support, inviting Carpentier to explore his ideas in a dedicated workshop outside Paris nestled among research labs for satellites and anti-aircraft missiles.

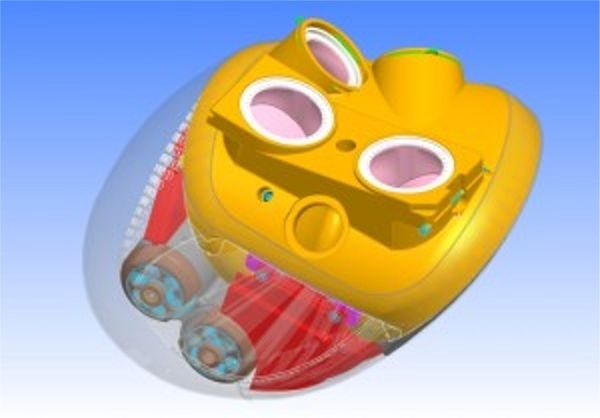

By 1993 Carpentier was given carte blanche to go forward with his mechanical heart, and spent the next 15 years and more than €15 million at EADS developing porous membranes, defining blood flow dynamics and continually reducing both the weight and the power demands for the device.

Further challenges included independent operation of two ventricles with separate ejection flows, inventing a new class of sensors to regulate blood flow and pressure depending on the patient's exertion level, and pushing down the heat production from the unit.

Patrick Coulombier, today the chief operating officer for the newly created Carmat, was assigned to the EADS heart project in 2001.

“The design brief was to approach the human heart as an on-board system similar to a satellite, completely autonomous, self-regulating, and where there is no possibility for intervention once the unit is launched,” he said.

“What began as a medical idea quickly entered the space I am familiar with of electronics, materials and mechanics,” said Coulombier, who previously led projects for the French Rafale jet fighter, missile systems and the Hérmes space shuttle.

Leading Carmat as CEO is Marcello Conviti, formerly the vice president for strategy and new business development at Edwards Lifesciences, a leading provider of heart valves.

Two senior executives in the cardiovascular industry who have joined the board of directors are the CEO of Sorin, André-Michel Ballester, and the former vice president for Medtronic's cardiac rhythm management, Peter Steinmann.

If clinical evidence supports Carmat’s ambitions, a biosynthetic artificial heart could create what CEO Conviti estimates to be a $16 billion market potential for heart replacement based on a global patient population of 100,000 with devices conservatively priced at $160,000.

31.08.2010