Experience

25 years of point-of-care ultrasound in anaesthesia

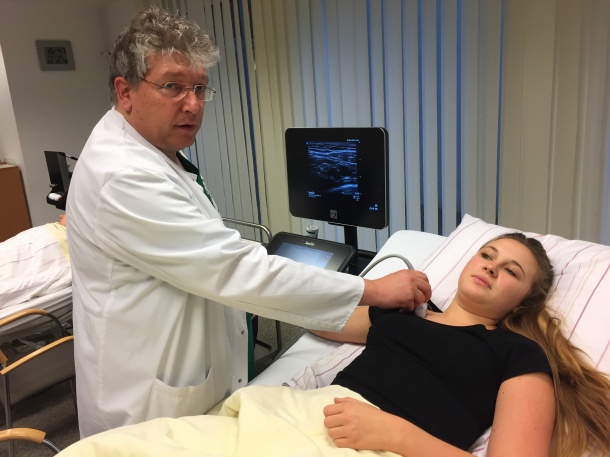

Dr. Thomas Grau, Head of Anaesthesia, Surgery, Intensive Care, Emergency Medicine and Pain at the Gütersloh Clinic, first studied ultrasound for a PhD on spinal imaging at Heidelberg University Hospital in the 1990s. 25 years on, he reflects on the role point-of-care ultrasound now plays in anaesthesia.

My first encounters with ultrasound were guided by efforts in Heidelberg to improve epidural anaesthesia in obstetrics. We identified that using point-of-care ultrasound to guide the needles could potentially help doctors to implement more effective epidurals more quickly, and might also reduce the complications that resulted from dural perforations. At the time, visualisation of this area was very superficial; there was very limited knowledge and the first thing we had to do was work on the ‘sono-topography’ of the spine. To begin with this was quite difficult, because the spine is surrounded by a lot of calcified structures and this creates a huge number of artefacts. Image quality was also not as good as it is now. However, we compared ultrasound images to CT and MRI, and were able to carry out some examinations on children, because they have less calcification and gave us better visualisation, and developed useful guidelines for scanning the spine and specifically the epidural and intrathecal spaces. At the same time, we were working closely with a well-renowned group in Vienna – led by Peter Marhofer and Stephan Kapral – who had already worked on and implemented methods for peripheral nerve blocks, such as ultrasound-guided supraclavicular blocks.

After Heidelberg, I had further opportunities to develop my skills in regional anaesthesia and implement more ideas for puncture techniques and pain control as one of the senior consultants at Europe’s biggest trauma healthcare centre, the University Hospital of Bergmannsheil in Bochum. The structure of this hospital has been very much influenced by its role in Germany’s employers’ liability association. This unique insurance system ensures that anyone injured as a result of their profession gets intensive treatment to compensate for their injury. The insurance goes some way to covering their loss of earnings, and hopefully helps them return to work as soon as possible. The higher level of funding available through this system ensures excellent surgical standards. From an anaesthetics point of view, this has meant a quite distinct, differentiated approach to treating acute and chronic pain and to improve mobility and mobilisation of injured patients, an approach that I have since adopted in my new post as head of anaesthesia department in Gütersloh.

I have now been in Gütersloh for six years and, on a personal level, one of the main reasons I moved here was the opportunity to work on a diverse range of anaesthesia and intensive care cases, a contrast from the specialist trauma centre at Bochum. Gütersloh is a medium-sized hospital of around 500 beds – 220 surgical beds, then another 270 beds for conservative medicine – covering a wide range of surgical specialties, including abdominal, thoracic, orthopaedics, emergency care, vascular, plastic surgery and reconstruction, gynaecology and urology. We perform about 11,000 anaesthesia procedures a year, for surgery, intensive care, emergency medicine, and have recently implemented chronic pain services in our treatment protocols.

When I first came to Gütersloh, the team there was not entirely comfortable with using point-of-care ultrasound to guide regional anaesthesia or as a diagnostic tool. We started to build confidence by using ultrasound guidance for placing central lines and then some relatively easy peripheral nerve blocks – interscalene and femoral. Doctors and managers soon saw that this technique was far quicker and safer for the patients, and cost effective too, so we developed a training initiative based very much on the courses I had previously run in Heidelberg and Bochum. In the last few years, we have held more than 30 courses in Gütersloh, with participants coming from other parts of Germany, as well as Switzerland, the Netherlands and Austria. The two-day courses are very comprehensive, including a significant amount of hands-on practice using the latest point-of-care ultrasound systems, including several provided by FUJIFILM SonoSite. We teach anaesthetists how to perform ultrasound-guided procedures safely, how to use ultrasound for diagnostic techniques when relevant and, crucially, how to avoid complications. The key issue is discussing what problems might occur while using imaging techniques in anaesthesia and how to deal with them.

For imaging in puncture techniques, the participants examine volunteers, looking at their upper and lower extremities, regions of the trunk, etc. We purposefully have live models of different shapes and sizes, and the participants get the chance to look at structures of interest around nerves, fascia, muscles and bone structures. It is very important that they recognize that while anatomy is similar in some people, the human construction plan is not 100 % perfect! I would estimate that only 70 % of patients present what you would call a fixed, ‘normal anatomy’. Around 30 % have a variation in their anatomy. That’s the key issue where ultrasound imaging has a big advantage. It doesn’t matter if the patient is three years old or 95, if they are big or small, if they are thin or fat, muscular or not; it doesn’t matter if their anatomy matches the textbooks or the anatomy atlases or not, using ultrasound is the perfect guide. You now know exactly how to proceed with injections and how to make an exact diagnosis. The reality in the operating room is that there are no ideal patients, variability and sometimes pathology is a rule of life.

For the last 20+ years, I have worked on improving puncture techniques, on detecting how deep to put the needle and catheters in under visual control, and the procedures have undoubtedly changed so much. The same is true of using ultrasound as a diagnostic tool. Although training programmes like ours are successful, funding is still one of the main issues that is restricting the use of point-of-care ultrasound all over Europe with ultrasound intervention. An additional support from companies such as FUJIFILM SonoSite is crucial. Procedures are faster and safer and more effective with ultrasound and, because of this more patients can be handled in less time. This effect can’t be translated into cost savings.

In many aspects there is still not enough awareness of the potential behind this technique but I am confident this will change. Sooner or later, I hope there will no longer be a discussion of whether you use ultrasound or not, it will simply be a part of every relevant procedure in anaesthesia.

11.11.2016