Article • Virus

The Zika mystery: scapegoat or villain?

Report: Brenda Marsh

From the beginning the accusation somehow beggared belief. A ‘mild’ virus was blamed for causing hideous malformations in babies’ heads. Brazil, a country suffering its worst recession since the 1930s, as well as political upheaval, became the focus of a worldwide healthcare scare.

Among mosquitoes enjoying a nice environment there one fairly innocuous ‘new kid on the block’ – Aedes aegypti – which, okay, is a vector for diseases – went hardly noticed when it first migrated to this country. Good heat, poor human dwellings surrounded by lots of stagnant water, all offered a comfy place to live and breed in a new country, with plenty of blood around for the ladies.

History and origins

Aedes aegypti, part of a mosquito family, hosts Zika, a flavivirus related to the viruses that transmit yellow fever, dengue, West Nile, and Japanese encephalitis to humans. It was discovered just under 70 years ago, and that’s important to remember.

In Uganda in1947, researchers on a Rockefeller Foundation investigation into jungle yellow fever, put a rhesus monkey – numbered 766 – into a cage on a tree platform in the Zika Forest. 766 was there to be bitten. Two days later, the feverish monkey was taken to the Foundation’s laboratory and its serum inoculated intracerebrally into mice. 10 days later those mice were ill. The researchers isolated from their brains the transmissible agent, later naming it Zika virus (ZIKV).

- In early 1948, in the same locale, ZIKV was also isolated from Aedes africanus mosquitoes. Serologic studies showed humans could also become infected. In 1956, ZIKV was transmitted to artificially fed Ae. aegypti mosquitoes and was transmitted to laboratory mice and a monkey.

- Nigeria, 1968: ZIKV was isolated from humans during studies and then also in 1971–’75; 40% of people in one study had neutralising antibody to ZIKV. Human isolates were also obtained from febrile toddlers and a sick 10-year-old.

- 1951-’81: Evidence of human ZIKV infection was reported from Uganda, Tan-zania, Central African Republic Egypt, , Sierra Leone, and Gabon, as well as parts of Asia – India, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines.

- 2007: An outbreak of ZIKV infecting about 75 percent of the population of Yap Island, Micronesia, revealed Aedes had travelled beyond Africa and Asia.

- 2011: Aedes alighted in French Polynesia, bringing outbreaks of dengue and chikungunya.

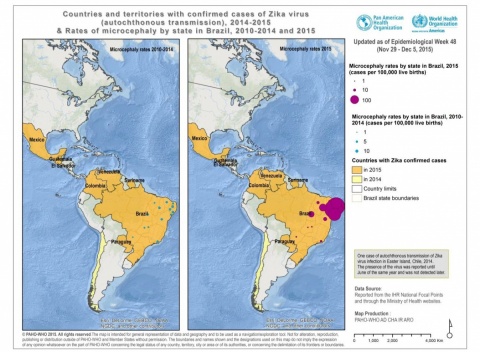

- 2014: Brazil was alerted to the arrival of a new virus in that country, after the FIFA World Cup. However, genetic analysis of the virus revealed that the strain was most like the one found in the Pacific – from which no football teams had come. Suspicion also fell on an international canoe event in Rio de Janeiro in August 2014, which drew competitors from Pacific islands. On the other hand, some thought it had come overland from Chile, where a traveller returning from Easter Island had a Zika infection.

- 2015: With 22 years’ experience, obstetrician and gynaecologist Adriana Melo, working in the state of Paraíba, in the poor semi-arid northeast Brazil, identified microcephaly in a 20-week-old foetus . Two weeks later, she found the same diagnosis for a 24-week-old foetus. News also came from Recife, in the neighbouring state Pernambuco, that Dr Ana van der and daughter paediatric neurologist Dr Vanessa van der Linden Mota had observed a peak in microcephaly foetuses and alerted the health ministry. Suspecting Zika to be the culprit in her two microcephaly cases, Melo contacted other specialists in her field and had sent amniotic fluid from the two mothers for analysis at a national science research institution in Rio de Janeiro. Three different tests detected the Zika virus in the fluid surrounding the microcephaly foetuses. Melo called for public-health officials to test amniotic fluid.

By mid-November the country’s Ministry of Health requested all doctors to report pregnancy cases where red spots appeared on the mother’s skin. Within a short time, the Ministry reported that suspected cases of microcephaly numbered 2,401 in 19 states and the Federal District, with 29 resulting in death.

The World Health Organisation (WHO), said to be still ‘stinging’ from criticism that it did not declare an international emergency over ebola, issued its international warning regarding ZikaV. Aedes became top international public enemy overnight.

Could ZikaV cause such huge harm?

Whilst rapid and expensive research is being undertaken globally to find the true cause of microcephaly, as well as a Zika vaccine, there is no big evidence that it could cause such developmental damage in the unborn. Yes, the virus has been found in amniotic fluid and brain tissue in a handful of cases. Also 1970s study showed the virus could replicate in neurons of young mice, causing neuronal destruction and more recent genetic analyses have suggested that strains of Zika virus might be undergoing mutations.

However, controversy erupted in Brazil first regarding the very definition of microcephaly - the yardstick by which to measure head circumference. After the identification of an excessive number of suspected cases, the Brazilian Ministry of Health declared a reduction in the cephalic perimeter measurement to suspect microcephaly, from 33 cm to 32 cm, instantly lowering cases.

Figures plummet

Microcephaly is an uncommon condition. In the USA, birth defects tracking systems estimated that the condition ranges from two babies per 10,000 live births to 12 microcephaly babies per 10,000 live births – totalling 25,000 microcephalic babies born there per year.

First declaring 2,401 microcephaly births, Brazil had to admit to a far lower number of confirmed cases, now reported to be around 460, but 3,850 are still ‘suspected’ and being investigated.

Rumours rumours …

People want tangible answers. Without them trust is lost. One popular theory among Brazilians has been that expired doses of measles, mumps and rubella vaccine have caused the gross head defects.

Just before 2016 dawned, Brazil’s federal government’s central information services tried to address this concern. It stated: it is ‘totally false that an expired batch of rubella vaccines, rather than the Zika virus, has caused the microcephaly outbreak’. In addition, health minister Marcelo Castro said he held ‘100 percent certainty’ that Zika and microcephaly are linked.

Where might he have gained such a positive conviction?

Certainly not from the group of Argentinian doctors who blame a larvicide, Pyriproxyfen, for the rise in microcephaly births. This has been added to people’s water tanks to combat mosquitoes. Although there is said to be no supporting scientific evidence of this cause, and the Health Ministry rejected the ‘non-scientific report, at least one Brazilian state ended distribution.

Theories theories …

Yoichi Shimatsu a science writer based in Hong Kong has an intriguing belief – that microcephaly cases were caused as a side effect of RIDL gene-transfer. ‘The so-called Death Gene blockage, using the GATA binding protein, can affect the same gene in human embryos as in the targeted mosquito pupae,’ he states. This protein has been introduced into male mosquitoes, which are then released as part of the OX513-A captive mosquito programme. Out there they successfully mate with wild local female mosquitoes and the protein enters the eggs to disrupt embyonic growth. The larvae self-destruct before adulthood. ‘However,’ writes Shimatsu, ‘these same mother mosquitoes can then transfer the dangerous protein into women, thereby seriously harming human embryonic development of the brain, nerves, heart and testicles. Damage to the GATA-1 protein in human embryos is associated with Down Syndrome, a brain disorder similar to Brazilian microcephaly.’

This population control by gene transfer science is ingenious. The OX513-A is produced by Oxitec Ltd, near Oxford, England. The firm’s description of various mosquito control methods found at http://www.oxitec.com/health/dengue-information-centre/vector-control/ is a worthwhile read.

Environmental issues

Amy Y Vittor MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine at the University of Florida’s Emerging Pathogens Institute, studies the interface between vector-borne disease and land use. She is studying another mosquito-borne virus, Madariaga, the cause of many cases of encephalitis in a Panamanian jungle. Her team examine ‘the association between deforestation, mosquito vector factors, and susceptibility of migrants compared to indigenous people in the affected area’.

‘In our highly interconnected world, which is being subjected to massive ecological change,’ she underlines, ‘we can expect on-going outbreaks of viruses originating in far-flung regions with names we can barely pronounce – yet.’Bild232009.GIF

So, what about deforestation? Resulting landslides of soil enter rivers and so deposit large amounts of mercury, which in water becomes methylmercury, an organic form of mercury – a neurotoxin, easily bioaccumulated in organisms i.e. entering the food chain through fish.

Brazil, a meat-eating nation, in recent years encouraged a fish farming industry. Current per capita consumption of fish is still low there – 6.8 kg per year. However, campaigns in 2003 focused on national and international markets for Brazilian aquaculture products. Much research shows that farmed fish can be high in methylmercury a known cause of microcephaly. Accidental leaching from aluminium processing might affect the food chain.. Checking for is presence in the microcephaly inquiry perhaps should not be ignored.

What we expected was that we’d have around three to four cases a year of microcephaly – which has been documented in the official sites. Then we noticed we had much, much higher numbers.

Sandra da Silva Mattos

Life before ZikaV

Sandra da Silva Mattos of the Círculo do Coração de Pernambuco and colleagues dug into medical records of over 16,000 babies born between 2012 and 2015 at one of 21 medical centres in badly Zika affected Paraíba state. Since 2012, they found a strikingly large number of babies – 4-8% were suspected of microcephaly within its broadest definitions, and the number peaked in 2014 – before Zika was detected in Brazil. ‘What we expected was that we’d have around three to four cases a year of microcephaly – which has been documented in the official sites,’ Mattos said in an interview. ‘Then we noticed we had much, much higher numbers.’

The researchers then narrowed the definition to extreme microcephaly cases and found the rates – 0.04% to 1.9% levelled to global reports of the condition. Still, hundreds of babies had microcephaly: the nationwide incidence of reported microcephaly in years before 2015 was below 200 annually. ‘It’s possible, she noted, ‘that a high incidence of milder forms of microcephaly has occurred well before the current outbreak, but that only those extreme cases, with classical phenotypes, were being notified. As the number of extreme cases increased over these past three or four months so did awareness of health professionals who started to notify milder forms.’ (Ref: Report published Feb. 4 in the Bulletin of the World Health Organization.

Mattos’s team did find an increase in the most severe forms of microcephaly in the last months of 2015, and doctors have reported a recent rise in the number of severe microcephaly cases in Brazil. Critical to understanding the degree of microcephaly is the need to standardise diagnostic criteria. Researchers at the Federal University of Pelotas, Brazil reported that ‘…the number of suspected cases relied on a screening test that had very low specificity and therefore over-estimated the actual number of cases by including mostly normal children with small heads.’

Currently, health coordinator Dr Adriana Scavuzzi and team at IMIP, a maternal and infant care hospital in Recife, is leading a case-controlled study in which 200 women are being interviewed regarding their lives and health history – including vaccinations received. Half the mothers have microcephaly babies. The rest are normal. Whilst she herself is ‘almost convinced” of a microcephaly-Zika connection, this could blow away at least some demanding questions. Meanwhile, a cloud of pesticide ‘fog’ looms over Brazil – prompting questions about the health of people liberally sprayed from moving vehicles, without prior warning, in the battle to kill Aedes – scapegoat or villain.

22.03.2016