TAVI will surpass heart surgery for aortic valve replacement

Implanting aortic heart valve prostheses percutaneously will become more common than surgical replacement, according to Dr John Webb

Each year the case grows stronger for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVI). And it is only six years since the procedure was introduced in Europe.

Each year the case grows stronger for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVI). And it is only six years since the procedure was introduced in Europe.

The strongest clinical evidence, which continues to fuel debate, is based on the first-generation of valves and delivery devices. It is also based on a population that was deliberately restricted to the very sickest of patients with an average age of 83 years and suffering from co-morbidities that meant they were unable to undergo traditional surgical aortic valve replacement (SAR).

Today, a new and improved generation of valves and delivery systems has arrived in the clinic. There is greater experience among interventional cardiologists, as well as improved outcomes for patients. Increasingly in Europe the procedure is being performed on ‘intermediate risk patients,’ those who suffer from a failing heart valve but who are typically younger and better able to withstand the rigors of traditional surgery.

How far are we from a turning point where TAVI will be preferred to surgery? The question is provocative because TAVI remains contentious in the cardiology community. Which patients? Who makes the decision? How reliable are these new valves? What about the high cost?

John Webb MD, from St Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, was a pioneer in the development of TAVI and has performed or supervised over 1,500 procedures worldwide. He is a leading authority on the technique and technology and author on over 300 publications in peer-reviewed journals, including Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Ahead of the meeting of ESC 2013, we asked Dr Webb for his views and future directions.

While it remains controversial, you have stated that TAVI will become a dominant approach to aortic valve disease.

Dr Webb: ‘I believe so, yes, because as we move into intermediate risk patients with newer devices in experienced centres, the risk of mortality becomes quite low and is competitive with surgery in intermediate risk patients with much less morbidity. Many centres are doing this on awake patients. Early discharges are becoming more common. Certainly patients are mobilised earlier at the hospital stage. Hospital stays are shorter. ICU stays are shorter. And I think the cost of TAVI is going to come down and become competitive with surgery for intermediate risk patients.’

Will TAVI replace open-heart valve replacement surgery?

‘There will always be patients who need open-heart surgery. There are obvious advantages to that approach. But I do believe that TAVI will become more common than surgical replacement. There are patients who do not have valves that are suitable for a transcatheter approach, or they have other things that need to be corrected. There are advantages to surgical valves as well for patients who can undergo surgery at relatively low risk.

‘In the future, I don’t think the issue is going to be whether patients are not candidates for surgery, but just that they would be better off with TAVI. This is the direction we are moving in Canada as well. We are asking who is better off with TAVI. The key message here is that the procedure needs to be done on patients who are going to benefit. This needs to be the focus. Cardiologists need to consider if their patient is going to have a significant improvement in quality of life; that they will live long and prosper.’

If you were to address colleagues at the ESC congress in Amsterdam, what would you tell them?

‘One of my big concerns about Europe is that this is a procedure that can be done at much lower risk by groups that have a high level of expertise. It is not a procedure that should be performed by low-volume operators. My concern is that there are an increasing number of low-volume centres in Europe and they can do better. There needs to be a balance between availability and ability. If I were to give a number, I’d say that individuals doing less than 50 cases in a year are not at a sufficient volume for expertise.

‘Also, there shouldn’t be groups competing within a single institution to the point where people who do not have sufficient expertise are performing this procedure. There should be programmes that involve both interventional cardiologists and surgeons who have relatively high volume practices and do high quality work.’

Many cardiologists may scoff at the idea that TAVI should only be performed in consultation with a ‘heart team’. Many have never been invited to share in the decision.

‘The true heart team is a relatively new concept. Traditionally, surgeons have made up their own minds about whom they will perform surgery on and what kind of surgery they will do. Interventional cardiologists are used to doing the same thing with coronary revascularisation.

But I think that when we have patients who are complex and there are different alternatives, it makes sense for there to be a group discussion about the best choices. ‘In the United States this approach has become artificial in some ways because the regulatory requirement is that both interventional cardiologists and surgeons must participate in all procedures. It seems to be overdoing it and may be driven by factors other than the procedure. The main principle to a heart team is that the patient is evaluated by a group with different skills and knowledge. There should be a discussion about which form of valve replacement is better with an evaluation and a discussion of the alternatives available. But the idea of a heart team does not necessarily mean they all need to be in the room doing the chosen procedure.’

Can you compare the development of TAVI in the USA and Europe?

‘In the USA the practice is influenced to a much greater degree by the requirements of the FDA, starting with the original trials. For example, in the PARTNER trial patients could only be admitted if they fulfilled very specific criteria and had a very high STS score, a high risk of mortality. Some of these patients are too old, too frail to benefit. So the bar is set perhaps too high in the USA, with the majority of patients at extreme risk for open heart surgery. That bar has been lower in terms of surgical risk for patients in Europe, driven more by the reduction in morbidity in some of the lower risk patients.

‘In Europe there has been a more clinically driven approach, which sometimes differs from what was required in the original trials.’

You have asked whether the high-risk patients enrolled in the original trials should be considered for the therapy in the first place.

‘That is a problem. Some patients are at such high risk that the benefits may be limited. Where the benefit might be much greater for patients who could be candidates for surgery, but the morbidity in surgery would be high. There tends to be less morbidity with TAVI than with surgery among intermediate to high-risk patients. In Europe, more and more the indication is becoming frailty, advanced age, without major co-morbidities that would make surgery a risk for these patients.’

An open question, especially as Europe moves to younger patients, is how long do these devices last?

‘We know that with in-vitro testing, in the lab, the TAVI valves last as long as surgical prosthetic valves. And we know that very, very few valve failures have been seen in the clinical experience to date. We have published our outcomes out beyond five years and failure of these valves is quite rare at that point. We can assume that they will fail eventually, as do surgical valves.’

Concern was expressed in Europe about patients in their 70s receiving valves for which the durability is unknown.

‘That’s fair enough to say and a very real concern. I guess I would argue that this is not the end of the story. At least with TAVI, valve replacement is a fairly repeatable procedure in that you can place a TAVI valve inside a TAVI valve.

‘One of the things people were most interested in (at the Transcatheter Valve Therapeutics event in Vancouver in June, 2013) was the new information on valve-in-valve implants where transcatheter valves are placed inside failed surgical valves. It seemed that in many people’s minds this is moving rapidly to a standard of care.

All valves, surgical and TAVI, will wear out in time and repeat surgery is always a higher risk than first-time surgery. Many of these patents, of course, have become older. There are lots of 70-year-old people who received a surgical valve and, as their valve fails, TAVI becomes an attractive option for these older patients.’

What is encouraging about the newer valves produced?

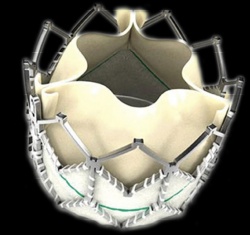

‘There are marked improvements in deliverability, profile and sealing with the newer generation of valves. Newer valves are, in general, more easily implanted. The lower profile means they go through smaller sheaths, through smaller arteries with a lowered risk of vascular injury. They tend to be more easily positioned, with features incorporated into the catheter, or in the valve itself, so they tend to be deployed at the correct height and the correct angle in the aortic annulus. So positioning is improving. They tend to have features that reduce paravalvular leak with the better seals.

‘In addition to improvements in the valves, there are dramatic improvements in techniques used. Early on, people had a limited idea of where to put the valve and now this is much improved. Early on there was poor understanding about how to pick the correct valve size, and here there have been dramatic improvements in understanding the three-dimensional anatomy in the annulus, which is related to imaging with 3-D CT and 3-D TEE.

‘All the new valves need to be proven. To some degree their use can depend on a predicate device. But if there is a dramatic change in how a valve functions, it really needs to be evaluated to see if it is going to be as reliable as a precedent valve.’

Profile:

John Webb MD is director of interventional cardiology, fellowship training, research at the Centre for Valve Innovation at St Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver. He is also an advisor to a number of biomedical companies and the government of Canada and McLeod Professor of Heart Valve Intervention at the University of British Columbia.

30.08.2013