Carefully selected devices reward MHH with 50% cost cuts

In intensive care units (ICUs) little can be automated to relieve staff pressures – with the exception of point of care testing (POCT)

The most up-to-date tools help to save costs as well as improve treatment quality, as demonstrated from Holger Zorn’s discussion with Josef Hollenhorst, Head of Strategic Investment Management, at Hanover Medical School (MHH) about the financial and clinical benefits of decentralised laboratory measurement devices

Supramaximal medicine often means that not just one or two specific parameters are required quickly but an entire profile – blood gases, metabolites and oximetry, inclusive of CO-oximetry, electrolytes, glucose and lactates. For example, for comatose patients admitted to A&E this type of comprehensive blood gas analysis immediately provides orientation. If the problem is metabolic or related to oxygenation this points towards a water-electrolyte imbalance, or diabetes – but if this is not the case, a neurologist or toxicologist is consulted. ‘Patients often move through the hospital contrary to predictable patterns,’ Strategic Investment Manager Josef Hollenhorst pointed out. ‘Each time we have a problem that doesn’t fit with the POCT profile at the place of treatment we run the risk of not sufficiently detecting and not scrutinising a critical situation, such as methemoglobinaemia or carbon monoxide poisoning.’

A sophisticated strategy

Up to three years ago the MHH had eight different types of devices from three different manufacturers available for bedside blood gas analysis, with fewer than 700 resources. ‘We wondered what would happen if we worked with just one supplier and one type of device and worked out that this would bring down the number of resources inclusive of spare parts to well below 100,’ he explained. ‘Based on this ratio alone, the rate of turnover for equipment with regards to POCT resources would increase by factor seven, and capital commitment would therefore fall drastically.

‘We realised that we had to adapt the profiles at a relatively high level and ensure that the same profiles were being measured everywhere.’ In 2011, the project was put out to tender across Europe. The requirements were high: around 550,000 samples a year in 34 locations requiring full profiles, with an availability of 99.7% and a back up across all locations.

‘Roche, Siemens, Radiometer, IL and Abbott replied to the tender, and all devices were evaluated in all areas in 14-day tests.’ Not only the handling was evaluated: ‘We measured energy consumption, and,’ Joseph Hollenhorst recalled, ‘we realised that, across the board, the new generation of devices almost halves energy consumption.’

More LEDs are used in the new devices than halogen bulbs – with operation around the clock over 365 days a year this factor cannot be underestimated. Electricity costs at MHH have doubled over the last seven years. A comprehensive look at decentralised laboratory diagnostics makes you realise that the picture manufacturers like to paint is not quite accurate.

‘One sample, one price – this slogan is just not true,’ he stressed. ‘POCT, much to the contrary, is an example of complex cost structures, i.e. ranging from acquisition to maintenance contracts, chemicals and liquid quality controls. Paper is often purchased as a generic, a savings option. Process-related, there is a colourful range of cost types and also of creditors.’

The total cost of ownership

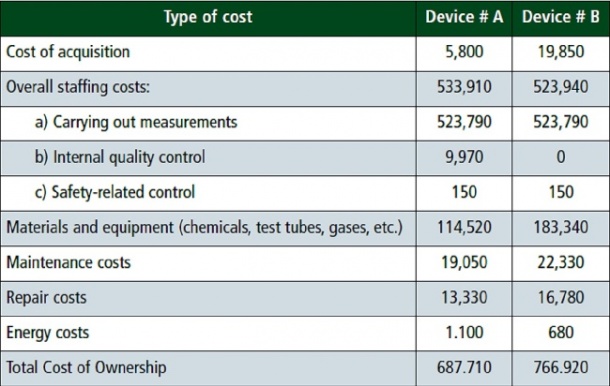

Barbara Weichselbaumer has evaluated the life cycle cost of POCT systems based on the current costs at MHH across the periods and used an approach that so far has mainly been known in the business world. The Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) concept captures the total costs of an acquisition across its life cycle. The central idea is that the acquisition price represents only part of the total cost and therefore should not be the only decision criterion for an acquisition (Source: Barbara Weichselbaumer. Total Cost of Ownership – A Feasible Approach in the Hospital? AV Akademikerverlag Saaarbrücken 2012, ISBN 978-3-639-38896-1). ‘The acquisition cost represents only 2.6% of the total costs over the life cycle in one type of device examined and in the other type only 0.8%,’ she determined. ‘The total personnel costs, especially those related to carrying out measurements, represent more than 65% of the total costs for both types.’ (See table).

Prior to the tender, the creditor-related costs were almost €4 per examination. Additionally, there were internal costs, the taking of samples and the time it took staff to carry out measurements. The decision was finally made to purchase a system where up to three samples can be simply deposited at the same time before the staff member can immediately return to the patient. The device provides fully automated and homogeneous sample mixing, scanning the barcodes, recognising them automatically, measuring them consecutively and transferring the results to the patient data management system (PDMS) via the laboratory information system (LIS).

Josef Hollenhorst has checked and projects: ‘With each measurement we save almost three minutes of staff time using this equipment. With around 550,000 samples this works out at 1.65 million minutes, i.e. the annual number of working hours for 14-15 nurses!’ The MHH strategy is to relieve pressure on nurses wherever at all possible. They are the most valuable resource on each ward and should spend as much time as possible with their patients, so this is to their advantage and represents real added value for the hospital.’

Meanwhile, the European tender has been implemented and MHH has 35 identical devices, in A&E, operating theatres, intensive care wards, cardiac catheter labs. Only the paediatric cardiac catheter lab has a different type of device supplied by the same manufacturer. Shunt measurements to determine cardiac defects, 7-8 measurements in minute cycles, require the shortest possible turnover.

The creditor-related costs per measurement were halved and cut to under €2 – a delivery model with a cheque-price. MHH virtually does not pay for the device, only for the finished result.

This price almost encourages even more measurements, Josef Hollenhorst declared, significantly happy. ‘Being able to achieve a result at less than two euroes a time and to say I need to readjust the ventilation, I’ve detected an increase in lactates at an early stage and could trace where it came from – the procedural as well as the cost benefit is always for the patient and the hospital.’

Profile:

Up to 2008, anaesthetist Josef Hollenhorst was managing senior physician at the Anaesthesiology Clinic at MHH and administered a turnover of €25 million in that role. From 2002-2008 he implemented the DRG cost per case calculations of the InEK (Institute for the Hospital Remuneration System) for the anaesthesiology department’s running costs.

Since 2008 he has managed the department for strategic investment management at MHH and, since August 2011, has also been head of the investment planning section. Since that year he has also overseen the preparation for the calculation of the investment-related flat rates of the German DRG Institute (InEK).

04.10.2013