From MIS to optimally invasive cardiac surgery

Since minimally invasive surgery (MIS) entered cardiac surgery in the mid-1990s it became unthinkable not to use this medical specialty. However, MIS procedures do not always result in the best outcome for patients.

Thus, at the German Heart Institute in Berlin (DHZB - Deutsches Herzzentrum Berlin) the preferred term is ‘optimally invasive’ surgery – a description attributed to Professor Roland Hetzer, the Institute’s Medical Director. In an August medical technology gathering, the concept was explained in a lecture by his colleague Professor Onnen Grauhan, Consultant at the DHZB Department of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery.

In early days of MIS the prevailing belief was that the smaller the incision, the better for the patient – and talk was of keyhole or buttonhole procedures. However, the term, at least in cardiac surgery, generally has a broader meaning. Prof. Grauhan: ‘Minimally invasive heart surgery nowadays is primarily aimed at minimising what is harmful and traumatic for the patient.’ Naturally, this continues to include the choice of incision and, if possible, minimisation, but not always exclusively – the reason why the preferred term at the DHZB is optimally invasive surgery. This more aptly expresses what really matters: finding the optimum level of invasiveness for each patient – and that doesn’t always have to be the procedure with the smallest incision.

Explaining the concept, Prof Grauhan spoke of mitral valve surgery. Here, a 10-15cm long incision for an anterolateral thoracotomy, i.e. incision on the side of the chest between the ribs, is optimally invasive and has clear advantages compared to a typical, 3-5cm minimally invasive incision. He cites four reasons why: First, cannulation for the heart-lung machine (HLM) can be done via the primary incision on the aorta and vena cava (left atrial approach) and does not require an additional incision in the groin; next, visibility is considerably better with the longer incision because the view offered by the cameras used with the smaller incision is not comparable to the direct view.

Third, myocardial protection, i.e. measures to protect the heart muscle during surgery, is easier when the incision is larger, as the quality of myocardial protection is easier to monitor.

His final argument for optimally invasive surgery is that a larger incision improves cardiac de-airing: ‘In our estimation and experience, de-airing is much easier with a larger incision. As banal as it may sound, you just take one hand and shake the heart a little, which makes the air rise up and out of the hear.’ Surgery is generally carried out with CO2 – if too much air reaches the brain via the blood this can cause significant damage.

However, it’s not only the ability to free the heart from any remaining air, but also the chance to have one’s hands in situ, which the professor feels is a clear advantage for a cardiac surgeon. In this example, the concept of optimally invasive surgery strikes a balance between traditional, median sternotomy and a classic, minimally invasive procedure.

However, one should mention that any intervention on the side of the chest, rather than via the sternum, would always be more painful in terms of wound healing. Mitral valve surgery at DHZB is always discussed with patients beforehand, along with any aesthetic considerations because, particularly in the case of MIS, the procedure involves several, smaller incisions for clamps, lighting and HLM cannulae, resulting in several scars. Although these tend to heal somewhat quicker than a longer incision, a patient might be concerned by this multitude of scars later.

Another example is bypass surgery. Patients often have several stenoses in different parts of their coronary arteries, or on the posterior wall, so that minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass surgery (MIDCAP) is not possible. In these cases, if possible the off-pump-coronary-artery-bypass (OPCAB) procedure, i.e. open-heart bypass surgery, is performed. ‘We also feel that OPCAB can be considered as optimally invasive here because it avoids the HLM and prevents limitations in renal and respiratory function and averts cerebrovascular events,’ Prof. Grauhan explains. However, in recent times, doubts have been raised about the OPCAB procedure due to unfavourable long-term results.

Coronary stents, an alternative hotly debated over the last two decades, he points out, are used at DHZB in agreement between cardiologists and cardiac surgeons according to the National Medical Guidelines on Chronic Coronary Heart Disease (2006). The recently published final results of the international, multicentre Syntax Study (Synergy between PCI with taxus and cardiac surgery) confirmed that, in around two thirds of patients with complex three-vessel disease or stenosis of the left main stem, bypass surgery is definitely superior to stent implantation. Therefore, he urged all cardiologists present to be more closely guided by the jointly developed medical guidelines in future. Too many stents, he says, continue to be implanted in cases where, taking into account current study results, bypass surgery would be better.

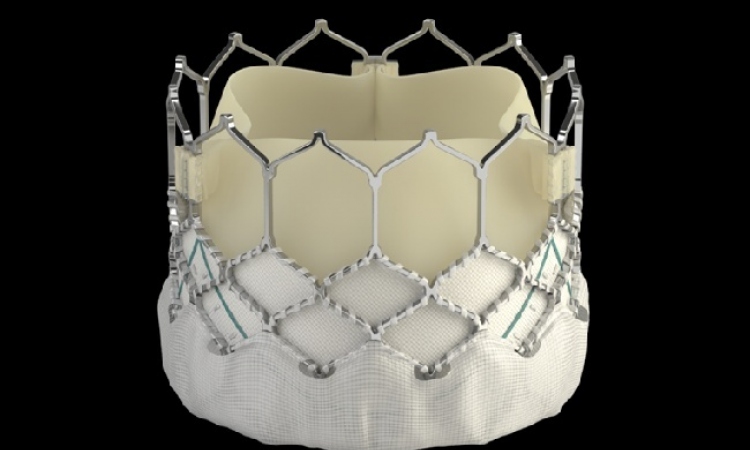

Prof. Grauhan is convinced that the trend will clearly continue towards minimalisation of incisions and interventional cardiac surgery, especially as patients are increasingly older so classic heart surgery is not an option. He does not want optimally invasive surgery to be perceived as a regressive concept but rather as a cardiac surgery strategy adapted to the overall outcome for the patient. The DHZB performs numerous interventional operations in the hybrid operating theatre (opened 2008), such as transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) and hybrid operations where surgery via incisions and catheter-based interventions are performed simultaneously on the same patient.

Profile:

Onnen Grauhan gained his medical degree and doctorate (thesis: ‘Man in microgravity”) at the Institute of Physiology, Free University Berlin. He was a resident at the department of Cardiothoracic Surgery at DHZB and the department of General Surgery at the Charité, University Medicine Berlin, and in 1994 became a consultant in DHZB’s cardiothoracic department.

In 1999, at the Charité Medical Faculty, his PhD thesis covered ‘Humoral rejection after Heart transplantation’. In the same year he became a University Lecturer at Charité. Since 2003 he has repeatedly stayed in Bosnia Herzegovina to support the development of a cardiac surgery unit at the University Sarajevo.

19.12.2013