Breast Cancer

Mammography screening with MR

Breast cancer screening is traditionally a mammography – ultrasound business but abbreviated protocols could enable more women to be imaged with MR and receive treatment earlier, a leading researcher will show during the annual Garmisch MR meeting.

“We don’t need to do so many sequences because a lot of data we collect during an MR examination is not that important for screening, a setting in which we usually only look for changes. We can pretty much lower the number of sequences down to 2 or 3 and make the exam shorter, so more tolerated by the patient and potentially cheaper,” Dr. Elizabeth Morris, Chief of the Breast Imaging Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York City, said ahead of the conference.

When screening for breast cancer timing is of the essence. Picking up cancer in its early stages means that patients will have a better chance of recovery and survival because cancer will be easier to treat.

“It is important it is to pick up cancer before you have clonal differentiation, i.e. before subclones of cells within the cancer undergo different mutations, which make it much more difficult to treat. If you pick cancer up very early, when it is still very small, there’s less of a chance that these mutations have actually occurred,” Morris said.

Using abbreviated MR protocols could make the modality more available to more women, as it is currently the only one enabling early detection, the researcher hopes.

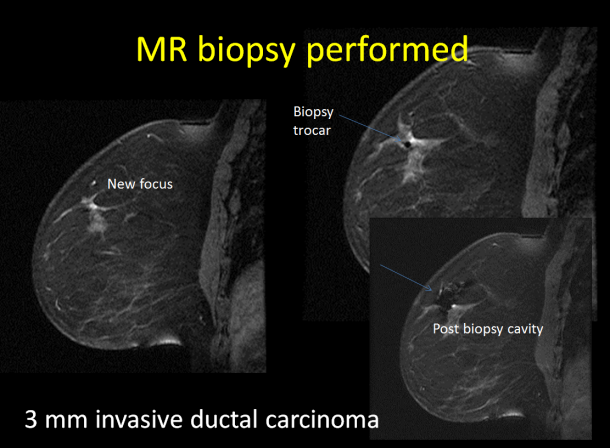

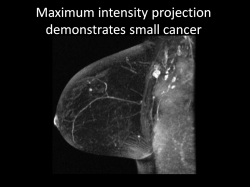

“It’s very important to investigate technology that enables us to see very small cancer. The technology we have right now is MRI because it shows vascularity, and when breast cancers are very small they create new blood vessels. We can see things that are very small on MR before we can actually see them on US or mammography,” she said.

Other contrast-based technologies could possibly pick up small cancers, for instance molecular imaging or targeted contrast agents for MR, but they are not available yet in the clinic.

Circulating tumor DNA that can be picked in the blood and liquid biopsy analysis can show potential gene abnormalities including specific mutations in BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 genes, which increase the risk of female breast and ovarian cancers, and are other interesting options for the future, according to Morris.

“Marie-Claire King, who discovered the BRCA 1 gene in 1990, said that BRCA testing should be mandatory and that every woman in the world should know if she is a carrier or not. It’s a fairly easy test to do. Many women are adopted or don’t know that they have a family history and if you know you’re positive, you can do something. No one is recommending that but it’s an interesting point of view. And in the future when it’s so much cheaper to get your genome sequence we could be moving toward that,” she said.

The American Cancer Society currently recommends using MRI in women who have a cumulative lifetime risk for breast cancer of more than 20%. However the group is reconvening on high risk screening guidelines.

“There’s a feeling that cumulative lifetime risks are not really that helpful and may not be very good for screening, and that it may be much better to look at a 10 year risk of developing breast cancer. That would be a much better indicator, based on the fact that you want to incorporate all the risks but you don’t want to send everyone to genetic testing,” she said.

MR remains the best modality to screen high-risk patients, but the absence of a national screening program and the variety of recommendations issued by different societies and organizations are making things very complicated in the United States.

“Currently what we’re doing is not enough. We miss a lot of breast cancers and they are way too big when we pick them up. Screening is not optimized and we need to do better. It’s really time for the US to think about a national effort to screen and that’s why we have so much variation in our screening practices here compared to Europe and other places,” she said.

The American Society of Breast Imaging, of which Morris is the president, recommends screening should be performed once a year in women in their forties, and then every two years from age 55.

“The 40s are the important decade to pick up breast cancer. When you’re younger it’s important to screen often because it increases the chance of picking up interval cancer, which is the worst kind. African American women notably have a much higher incidence of breast cancer in their 40s than later, so it’s very important in that age group or group of women compared to women in their 60s,” she said.

Women who have a family history and have dense breasts, another well-known risk factor because it can mask breast cancer, also need to be paid more attention.

Profile:

Dr. Elisabeth Morris is Chief of the Breast Imaging Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) and Professor of Radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College and the Larry Norton Endowed Chair.

She is the president of the Society of Breast Imaging and a fellow of the American College of Radiology and International Society of MR in Medicine.

Her research focus is on how best to use newer techniques such as MRI for early breast cancer detection and to improve the workup of breast lesions. She has written or co written over 150 papers, chapters, and books about breast disease with an emphasis on the use of MRI. She has lectured at over 300 conferences.

Currently, she chairs the MR section of the ACR BIRADS® Lexicon. She has authored a book “Breast MRI: Diagnosis & Intervention”. Her recent research efforts have involved looking at imaging biomarkers to assess risk and treatment response.

02.03.2017