Article • Brain functions transfer

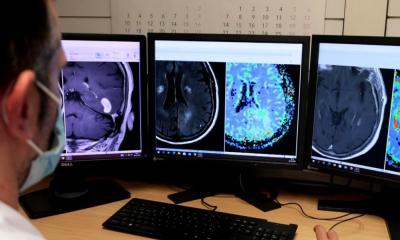

Pioneering cancer surgery

Brain cancer treatment is taking a major step ahead as Spanish surgeons pioneer a new technique that spares language and motion functions. This splendid development might even one day result in epilepsy surgery.

Report: Mélisande Rouger

A significant number of brain tumour cases have long been considered inoperable due to the extent of the lesion into ‘eloquent’ areas, meaning those that control vital functions such as language and motion. A team of Madrid-based surgeons are now injecting new impetus to brain tumour therapy, by enabling cancerous tissue resection without damaging brain function.

Dr Juan Barcia, study coordinator and head of the neurosurgery department at San Carlos University, in Madrid, explained how the idea of transferring function first arose. ‘Back in 2007 one of our patients presented an aggressive tumour that we couldn’t fully extirpate. Typically, these patients died, because we couldn’t touch these brain areas. So we thought of moving functions to other, healthy areas nearby, by stimulating them,’ Barcia explained, following the recent publication of his results in the Journal of Neurosurgery.

In his first attempt to migrate function, Barcia used transcranial magnetic resonance – and failed because stimulation time was too short. Inspired by equipment used in epilepsy treatment, he then decided to place a grid of electrodes to continuously stimulate and thus induce plastic reorganisation.

Most previously demonstrated eloquent areas within the tumour were silent, while there was new functional activation of brain areas in the same region or toward the contralateral hemisphere.

Prof. Juan Barcia

First, he operated on his awake patient and removed the part of the tumour devoid of function. Then, he placed the grid directly over the areas affecting function. Through the grid, he provided continuous and increasingly intense cortical electrical stimulation to the functional areas to artificially cancel function and enable the brain to transfer function to nearby areas. The intervention was coupled with appropriate behavioural training – also called pre-habilitation – in which the patient repeats the function that is being transferred over and over. Three weeks later, when the maximal stimulation voltage in all active contacts induced no functional deficit, he successfully resected the tumour more extensively.

Between 2009 and 2014, Barcia successfully operated on four more patients with WHO Grade II and III gliomas affecting the eloquent areas. He used intraoperative mapping and functional MRI to demonstrate plastic reorganisation. ‘Most previously demonstrated eloquent areas within the tumour were silent, while there was new functional activation of brain areas in the same region or toward the contralateral hemisphere,’ Barcia explained.

The role of behavioural training is fundamental. ‘Pre-habilitation with continuous cortical electrical stimulation and appropriate behavioural training prior to surgery accelerate plastic changes,’ he added. ‘This can help to maximise tumour resection and, thus, improve survival while maintaining function.’

So far the technique has only been used in gliomas, but Barcia believes it could also work in other tumours and further applications, such as epilepsy surgery. The project attracted very positive response from the field after its presentation during the annual meeting of the American Society of Neurological Surgeons in Chicago and the European Association of Neurosurgical Societies last year in Madrid. ‘We’ve been approached by different groups to design a European study,’ he said. Patients also contacted Barcia and his team after their work was featured in one of Spain’s most popular radio shows last May.

08.11.2016