Article • Immunotherapy, iRecist and complications

Lung cancer imaging (in a post-Covid world)

The evolving area of immunotherapies in lung cancer and the role of iRecist treatment assessment protocols were investigated during a virtual session organised by the British Institute of Radiology (BIR).

Report: Mark Nicholls

Consultant radiologist Dr Charlie Sayer, specialist in lung cancer imaging at the Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals Trust, South of England, focused on immunotherapies, the limitations of traditional response assessment, and the role of iRecist in the context of NSCLC (non-small-cell lung carcinoma), and also examined assessment of immune-mediated toxicities and what radiologists need to be aware of in this post-Covid-19 pandemic.

The session was part of a BIR lung cancer study day, ‘Lung Cancer Imaging: Update for the not-so-new normal’, which provided updates in lung cancer imaging.

In his presentation, ‘Immunotherapy, iRecist and complications in NSCLC (in a post-Covid world), Sayer said: ‘Cancer has an ability to avoid immune detection, now known as emerging hallmark malignancy. Essentially, we are aware it can express certain cell receptors which can evade the immune system, essentially telling the immune system there is nothing to see.’

Sayer pointed to a study of resected lung cancers and how in cancers with high immune evasion capacity the prognosis was significantly worse. Immune checkpoint inhibitors have been developed to target these pathways and work by activating T cells that have been suppressed or evaded the tumour. Receptors of most interest in lung cancer are PD-l1 and PD1, with Pembrolizumab the most commonly used agent in the UK. ‘What we are seeing is patients with Stage 4 NSCLC, previously treated with chemotherapy or radiotherapy, with up to 20% now achieving survival up to five years,’ he said. “This is even better if we look at patients who are treatment naïve and receiving immunotherapies, with around half having an overall survival of two years.’

Combining chemo and immunotherapy

iRecist may seem intimidating but is actually very simple

Charlie Sayer

Good radiological responses are also being seen with combinations of chemo and immunotherapy, Sayer added. Looking at response assessment, he referred to Millar’s criteria from the 1980s with a ‘common language’ to describe radiological effects in clinical trials, WHO guidelines and Recist and Recist 1.1, but he stressed: ‘It is important to note that these were never intended for use outside clinical trials and have limitations in practice.’

As tumours respond differently to immunotherapies compared to chemotherapies, the iRecist consensus guideline was developed by the Recist working group for the use of modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (Recist version 1.1) in cancer immunotherapy trials, to ensure consistent design and data collection and facilitate the ongoing collection of trial data.

Sayer, who noted that Recist 1.1 has limitations for immunotherapy response assessment, explained that a number of tools have been developed to look at immunotherapy response to avoid the potential premature cessation of therapies and to capture atypical responses. ‘The most recent iteration is iRecist, which was published in 2017, and we are now using this in clinical trials. iRecist may seem intimidating but is actually very simple. If you are familiar with Recist 1.1 it is the same definitions that are used for assessment until we see a progression radiologically; from that point iRecist begins.’

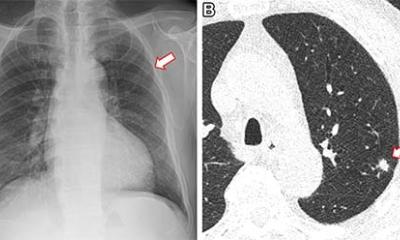

Hyperprogression is an important concept with rapid progressive disease following initiation of immunotherapy and is associated with poor outcome, he pointed out and also touched on immune-related toxicities and immune-related pneumonitis. ‘If we think of the immune system being in a delicate balance, too much immune function can result in autoimmune disease, too little immune function can leave us susceptible to infection or malignancies,’ he said. ‘Immune related pneumonitis is more common in NSCLC patients, and associated with increased mortality. It is the most important immune-related adverse effect to be aware of in lung cancer patients because of its ability to worsen the overall prognosis.’

There are also post-Covid-19 considerations, with the pandemic having increased the complexity of cancer care. ‘This is now a balancing act – in balancing the risk of treatment delay versus harm from Covid-19,’ Sayer observed. The disease, he said, is no worse having Covid-19 while being treated with immunotherapies, and this might be to do with ‘ramping up’ the immuno-system. Immunotherapy is now deemed by the NHS as a Covid-friendly cancer treatment. ‘This is because of its ease of delivery, it can be given orally, in the community or at home, and the ability to have treatment pauses on patients who have received immunotherapy for some time.’

Profile:

Dr Charlie Sayer is a consultant radiologist at Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals Trust in the south of England, with an interest in thoracic, head and neck and oncological imaging. He completed a two-year fellowship in cardiothoracic and body imaging in London during which he conducted academic work in lung cancer surveillance imaging, pulmonary hypertension and interstitial lung disease. Recently, he has co-authored book chapters and papers on lung nodule imaging, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, lung cancer screening and pericystic lung cancer.

19.11.2020