Article • Emergency Imaging

Forensics identify victims and terrorists

‘I am sorry, the electricity will be cut off because we’re going to simulate an attack, or emergency exercise, this morning,’ explained Dr Wim Develter, when he suddenly delayed his interview with Mélisande Rouger of European Hospital. They were about to discuss computed tomography, and its role not only in advanced healthcare and other more unexpected areas, such as the arts and forensics, but in recent years as a forensic tool in police investigations into terrorism. During ECR 2017, this leading forensic pathologist, from Leuven University Hospitals, will describe the procedures and practices within his work.

Seasoned forensic pathologist Dr Wim Develter has worked on disaster victim identification (DVI) in four major catastrophes, including the terror attacks in Brussels airport in Zaventem, in March 2016.

At the department of Forensic Medicine Department at Leuven University Hospitals, in the Netherlands, he trains forensic pathologists. In its DI and crime scene investigation work, the department organises simulations in which an invasive attack or disaster takes place and the personnel must act accordingly.

In his latest exercise, Develter put mannequins with prostheses in a plane to train staff towards the identification model as well as to test whether Leuven’s facilities were big enough and if everyone was sufficiently trained. ‘We also tested the psychological support for the families. Shortly after that exercise, the Brussels bombings occurred, so we were well prepared,’ he added.

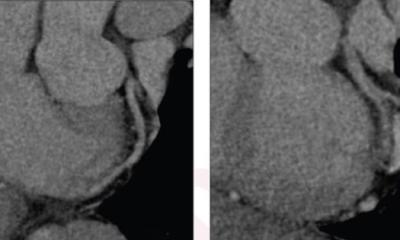

The examination of disaster victims and their remains often begins with CT exams, first to rule out danger in the bodies – hidden explosives or biohazard – and then to organise the identification process (complete bodies, body fragments or body parts). CT also helps by showing the pathologists whether the victims were wearing jewellery or metallic devices, such as prostheses, at the time of the disaster, information that can help to identify them. Once this information is gained, the forensic team can track down where he or she received surgery or where objects were bought.

Develter could not speak of the contents of the on-going investigation regarding the Brussels attacks at the time of our interview, but he said the identification process of a terrorist or victim is similar. ‘After an attack you have a lot of extra information that can be useful for your investigation. I am one of the leading forensic pathologists in this enquiry, so I cannot say anything about the contents of the investigation because of the instruction’s secrecy,’ he said. However, during the ECR, he will share his experience in disaster victim identification in other mass disasters.

As a trained pathologist, Develter started working in forensics in the wake of the Tsunami in Thailand in 2004 and, a decade later, worked on the MH17 Ukraine plane crash. In both events, high-end CT imaging proved very helpful in victim identification but its use depended very much on the circumstances of the event.

Whilst the plane crash victims could be related to a passenger list, things were far more difficult after the Tsunami. ‘It was an open disaster, people were in their swimsuits; they were not wearing any clothes, or had cell phones or keys, there was nothing to identify them.

‘DNA was very important then and we were very lucky that China offered free DNA investigations for all victims.’

The aftermath of the tsunami, which caused 227,000 people from all over the world to lose their lives, became the catalyst to improve international Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) protocols.

‘We realised that we needed to have an international protocol because we were all working in more or less the same way, but some countries, such as Germany and the UK, had much more experience than others. So the results could be different and that’s something that cannot be; if you are performing one (international) investigation everything needs to be on the same level and by the same criteria,’ Develter explained.

Whereas in Europe the team often relies on mobile CT services, which can be available within one or one and a half days in the entire continent, protocols can change according to the situation and the forensic team must adapt to local circumstances. ‘Everything is digitised now,’ he pointed out. ‘Back then, twelve years ago in Thailand, everything was written on paper.’ In addition, Develter and colleagues dealing with the tsunami victims had to choose between ventilation and lighting to be able to operate their devices, including the X-ray machines.

Things were expedited after Thailand; forensic pathologists established a protocol, which they extend annually. The International Criminal Police Organisation (Interpol) in Lyon, France, is responsible for establishing and revising the protocol every four years. Every year Develter and his DVI pathologist colleagues participate in an Interpol meeting to discuss the approach to global disasters, and exchange experiences and discuss protocols.

His field has also benefited tremendously from popular TV series such as CSI. ‘Forensics became popular a few years ago thanks to these series. If you are not well known it’s hard to find funding or grants for scientific projects. Though still tough, that (program) has certainly helped our discipline. It’s an upward spiral.’

The field is multidisciplinary, among other specialities involving toxicology, microbiology, biochemistry, radiology and pathology and police investigative skills. ‘You need all these disciplines to answer just one question: What happened? That’s why the other fields are also interested: we’re all working to solve a mystery.

Profile:

Wim Develter MD is a trained clinical pathologist and an expert in corporal damage. As such, he specialises in forensic medicine in the Department of Forensic Medicine at Leuven University Hospitals. He is also Secretary for the Royal Belgian Society of Legal Medicine.

Event information:

EM 1 - Emergency radiology

Friday, March 3, 10:30 - 12:00

Room: B Session

Type: ESR meets Belgium

Topic: Emergency Imaging

Moderators: G. M. Villeirs (Gent/BE), P. M. Parizel (Edegem/BE)

03.03.2017