Oncology

Molecular genetics and proteomics

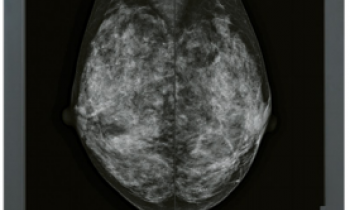

Women with metastatic breast cancer know they have a slim chance of long-term survival. The question is whether personalised therapy could extend their lives.

Report: Cynthia E Keen

The combination of molecular profiling and proteomics to create individualised breast cancer treatment is continuing to show promise, with the results of the second Side Out clinical trial published online 11 September 2014 in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment.

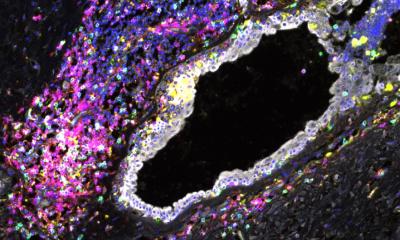

Proteomics is the use of molecular biology, biochemistry, and genetics to analyse the structure, functions and interactions of proteins produced by the genes of a particular cell or tissue. Proteomic tests provide information that genetic analysis cannot. Genetic analysis can identify all the proteins that a tumour is capable of making. Proteomics measure the activity levels within the signalling pathways of individual tumours – pathways that drive the growth, activity and reproduction of cancer cells, and thus identify the proteins that are responsible for tumour growth.

The two pioneering Side-Out clinical trials conducted between 2010 and 2012 created individual therapies for women with advanced breast cancer metastases who had already received multiple treatments. Their objective was to determine if individualised treatment could produce better outcomes than their most recent treatment – and they did.

‘Genomic sequencing and proteomic pathway mapping of metastatic lesions have recently shown that the molecular factors driving the growth or drug resistance of metastatic colonies may be quite different from the primary tumour from which they are derived. What this has meant is that conventional treatments may not be very effective, as evidenced by the fact that metastatic breast cancer patients tend to undergo a series of different consecutive treatments, each with diminishing effectiveness,’ said Professor Lance A Liotta MD PhD, co-director of the Centre for Applied Proteomics and Molecular Medicine at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia, USA.

Dr Liotta discussed the Side Out trials, of which he is a co-investigator, with European Hospital. These were sponsored by the Side-Out Foundation, a U.S. organisation of volleyball players and coaches dedicated to making significant and identifiable differences in the lives of breast cancer patients. He has spent much of his career investigating the process of tumour invasion and metastasis at the molecular level.

‘These trials are exciting because this is the first time that treatment for metastatic breast cancer has been individualised. Participants’ metastatic lesions were biopsied and profiled. A multidisciplinary treatment selection committee then reviewed the patient’s data, and recommended therapeutic options based on the molecular findings. The most effective drug or drugs identified were either donated by pharmaceutical companies or paid for by the foundation,’ he said.

‘Our primary objective was to determine if the individualised therapy would produce 30% longer time to progression as compared to the patient’s most recent prior treatment. A secondary objective was to determine the percentage of time that the patient’s oncologist would have selected a different treatment than that selected by the investigators.’

21 patients participated in Side-Out I, six of whom had partial responses and 12 had stable disease. The disease control rate was 72%. Forty percent experienced 30% or longer time with a progression-free response. Side-Out II treated 25 patients, who had had undergone anywhere from three to 12 prior treatments. Five had partial response and eight had stable disease. An addition 4% – or 44% of the total experienced 30% or longer time with a progression free response. Significantly, none of the physicians of any of the patients had selected the treatment that was actually administered.

‘This type of individualised therapy shows huge promise,’ Liotta confirmed. The Side Out Trials target Future research that stems from the Side Out Trials may greatly benefit metastatic breast cancer patients by identifying and delivering the most likely effective treatment as soon as metastasis is identified. At a minimum, this could eliminate treatments that won’t be effective because of the molecular differences of the metastatic lesion compared to the primary one.

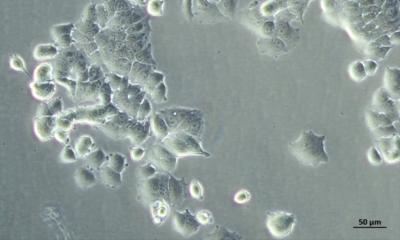

On the other end of the time course of cancer, Dr Liotta and his colleagues are currently conducting a breast cancer trial aimed at stopping breast cancer before it starts. The PINC trial (Preventing Invasive Carcinoma with Chloroquine) is a neo-adjuvant trial accepting all patients diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Women with a biopsy diagnosis of DCIS receive a one-month oral dose of an anti-autophagy inhibitor before surgical therapy of their DCIS lesion.

The advantage of the DCIS trial design is that the DCIS lesion size and proliferation index can be compared before and after therapy in the same patient, so the therapeutic outcome is known immediately.

The team hopes that cancer treatment centres in Europe will consider enrolling. The future goal is to develop a short-term oral therapy that kills breast cancer precursor lesions to prevent breast cancer.

20.01.2015