Article • Functional neuroradiology

When music lights up the brain: insights from fMRI

At the JFR 2025 (Journées Françaises de Radiologie), the annual meeting of the French Society of Radiology, an organist and a neuroradiologist came together to share a story that bridges two worlds rarely seen in dialogue – that of sound and that of images. One listens, the other looks. Yet both try to understand the same mystery: what happens in the human brain when music takes control?

By Mélisande Rouger

© logo3in1– stock.adobe.com

It all began, as many collaborations do, around a dinner table in Paris.

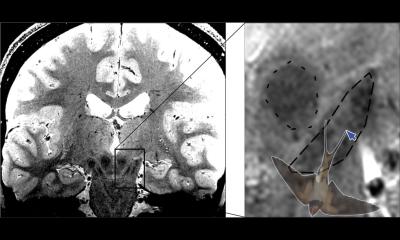

Charles Mellerio, a neuroradiologist specializing in functional imaging, had recently been part of a TV documentary about conductor Alain Altinoglu. Curious to see what a maestro’s brain might look like while leading his orchestra, he had placed the conductor inside an MRI scanner and watched colours bloom across the screen – regions of sound, movement, emotion, and attention lighting up all at once. The findings would later be published in the Journal of Neuroradiology.1

Months later, at that dinner, he met Anne-Isabelle de Parcevaux, a professional organist from Paris and Versailles, equally fascinated by neuroscience. As they talked, she helped him reinterpret those images through the eyes – and the ears – of a musician. What had seemed like random activations suddenly made sense. A zone linked to the perception of the throat, for instance, turned out to be involved in inner singing – that silent melody many musicians “hear” as they play.

When musicians become their own experiment

From that exchange, a scientific article was born. And from that, a collaboration.

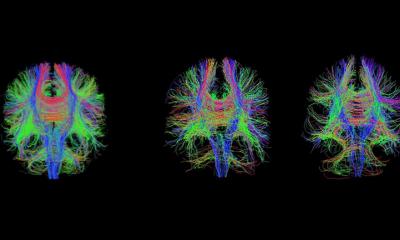

Together, Mellerio and de Parcevaux began exploring the brains of different musicians – violinists, flutists, pianists, conductors, and singers – using functional MRI to capture what happens when they imagine playing or listening to their own music.

The results were striking. Compared to non-musicians, their brains lit up like symphonies – engaging not only auditory regions but also motor areas, emotional centers, and even the zones of language and vision.

As Charles Mellerio explains, ‘A professional musician doesn’t just hear music. Their brain anticipates it – it prepares the movement, the emotion, even the physical gesture of playing.’

The hidden choreography of the brain

Each musician’s brain revealed its own signature. The violinist’s motor cortex glowed stronger on the side controlling the left hand. The singer’s brain activated the areas for breath and articulation. The pianist’s visual-spatial regions were hyperactive, guiding her hands across an imagined keyboard.

Even when perfectly still inside the scanner, their brains were dancing.

Anne-Isabelle smiles as she recalls these findings: ‘It’s fascinating to realize that what we feel intuitively as musicians – the coordination, the emotion, the inner singing – all have visible traces in the brain. Seeing it on an image makes it even more real.’

The composer’s mind: where thought becomes sound

In a second phase of their research, the duo studied improvisation. Composer and organist Thierry Escaich was asked to create music inside the MRI, silently, without touching an instrument.

When he imagined a baroque fugue, the visual areas of his brain lit up – as if he were reading an invisible score.

When he turned to romantic music, the emotional orbitofrontal cortex became dominant.

And for contemporary creation, it was the analytical prefrontal zones – those of logic and planning – that took over.

As Mellerio puts it, ‘Each musical style tells a different story in the brain. Bach’s architecture, Chopin’s emotion, Boulez’s mathematics – they all use different neural pathways to express creativity.’

Music as a mirror of the mind

For Anne-Isabelle de Parcevaux, this journey into neuroscience is more than an experiment - it’s a new way of hearing herself. ‘As musicians, we work so hard on technique that we sometimes forget how complex our perception really is. Seeing the brain in action reminds us that music is not just an art – it’s a full-body experience, one that involves movement, memory, emotion, and thought all at once.’

Their joint work, presented at JFR 2025, reveals not only how music transforms the brain, but also how curiosity – between two disciplines, two languages, two ways of seeing – can itself become a form of harmony.

Profiles:

Charles Mellerio, PhD, is a neuroradiologist at Paris University Hospital Group Psychiatry & Neuroscience and Northern Imaging Center in Paris, France. He trained as a radiologist at Claude Bernard Lyon 1 University and completed his PhD studies in neuroscience at Paris Cité University.

Anne-Isabelle de Parcevaux is an organist at Eglise St Ignace in Paris and Cathédrale de Versailles in France. She is also a Master’s student in Neuroscience at Sorbonne University and she graduated in arts medicine and music studies at the National Conservatory of Dance and Music and Saint-Maur-des-Fossés Conservatory in Paris.

19.12.2025