Image source: Adobe Stock/Tom

News • Deadly heart inflammation

Hope for first blood test to detect myocarditis

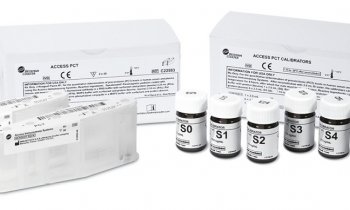

The first blood test to diagnose inflammation of the heart muscle (myocarditis) could be in use in as little as a year, following the discovery of a molecular signal in the blood by researchers funded by the British Heart Foundation (BHF).

The research, published in the journal Circulation1, offers hope of a quick and cheap way of diagnosing the condition.

Myocarditis is a difficult condition to diagnose. Symptoms include a temperature, fatigue, chest pain and shortness of breath, which can all be easily mistaken for other conditions. The gold standard method for diagnosis is a heart biopsy, an expensive, invasive, and risky procedure which can sometimes still miss signs of the condition. It is estimated that one young person dies suddenly every week in the UK due to previously undiagnosed myocarditis.2

Myocarditis is a notoriously tricky condition to diagnose and sadly some patients will suffer irreversible damage to their hearts because of the lack of accessible diagnostic tests

Nilesh Samani

Now, a team of researchers led by BHF Professor Federica Marelli-Berg at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL) have found that the presence of T-cells – a type of white blood cell – expressing a molecule called cMet in the blood strongly indicates that a person has myocarditis. They say that cMet-expressing T cells levels could be detected through a routine blood test that could cost less than £50 with results available within hours. The researchers hope that this finding will improve diagnosis of myocarditis and help people to get the treatment they need earlier, reducing the risk that they will develop life-threatening complications such as abnormal heart rhythms or heart failure.

In the study, researchers compared blood samples from several groups of patients, including 34 people with a final diagnosis of myocarditis. This showed that patients with myocarditis had significantly increased levels of T cells with cMet on their surface compared to other groups, including heart attack patients, and those with no medical condition. These findings add to the evidence that myocarditis is an autoimmune condition. The team found that cMet-expressing T cells become activated by molecules expressed by heart cells, producing an immune reaction against these cells that leads to inflammation of the heart muscle. The researchers also discovered that in mice, T cells with the cMet molecule seemed to have a role in driving the development of the condition. Blocking cMet with a widely available drug reduced the severity of their myocarditis.

The team will investigate this finding further in future studies and hope it will help them to develop the first targeted treatment for myocarditis. Professor Federica Marelli-Berg, British Heart Foundation Professor of Cardiovascular Immunology at Barts and the London, QMUL, said: “Early intervention is crucial when treating myocarditis as, in some cases, it can be only a matter of weeks between the onset of symptoms and development of heart failure. But without a diagnosis doctors can’t offer their patients the right treatment. We think that this test for myocarditis could be a simple addition to the routine blood tests ordered in doctors' surgeries. When viewed in combination with symptoms, the results could allow GPs to easily determine whether their patients have myocarditis. While we still need to confirm these findings in a larger study, we’re hopeful that it won’t be long until this blood test is in regular use.”

Professor Sir Nilesh Samani, Medical Director at the British Heart Foundation, said: “Myocarditis is a notoriously tricky condition to diagnose and sadly some patients will suffer irreversible damage to their hearts because of the lack of accessible diagnostic tests. This blood test could revolutionise the way we diagnose myocarditis, allowing doctors to step in at a much earlier stage to offer treatment and support. It would also reduce the need for the risky, invasive tests currently used, saving the NHS time and money and freeing up vital resources.”

Source: British Heart Foundation

24.11.2022